The African polyherbal mix Feug Ya Dzal reduces the CAE tumor marker values, fibroids’ number and volume: cases’ report

Cite: Menvouta M. S., Prummer A. G., Njikam N. Y.-L. and Zoa V. (2022). ‘The African polyherbal mix Feug Ya Dzal reduces the CAE tumor marker values, fibroids’ number and volume: cases’ report’. The Int. J. Holist. Sci. Innov. Dev., 11(3), pp. 133–150.

The African polyherbal mix Feug Ya Dzal reduces the CAE tumor marker values, fibroids’ number and volume: cases’ report.

Menvouta M. Soline1, Prummer A. Gabrielle2,3, Njikam N. Yves-Laurent4 and Zoa Victor3

Corresponding author: Menvouta M. Soline, menvoutasoline@gmail.com - Accepted: October 2022 - Published: November 2022

ABSTRACT

Uterine fibroids, also called leiomyoma, fibromyoma, or myoma, are the most common solid benign tumors affecting millions of women of reproductive age. Many women with uterine fibroids do not have any symptoms. Many frequently experience heavy or painful periods; prolonged menstrual periods; bleeding between periods; pelvic pain or low back pain; fullness in the lower abdomen, infertility, multiple miscarriages, or early onset of labor during pregnancy. A 33-year-old female patient approached the outpatient service with complaints of pelvic discomfort. Ultrasound scan revealed 6 fibroids measuring from 10 to 52 mm. She was recommended to have tumors surgically removed. However, the patient was not willing to undergo surgery and was in quest of nonhormonal treatment. She was treated with the African Traditional Medicine (ATM) mix Feug Ya Dzal capsules and tea. Treatment was continued for 19 months with a follow up once a month. A periodic ultrasonography revealed the shrinking of fibroids combined size by 59% (9 cm overall) and number (from 6 to 2). A follow up scan also revealed that the 40 mm submucosal fibroid had become undetectable by sonography within the first 6 months of treatment. Meanwhile, a 58-year-old male patient diagnosed with stage IV colon cancer was being treated using chemotherapy. Experiencing no apparent improvement, the patient requested complementary medicine. With chemotherapy treatment alone, the carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) value monitored within a month increased from 212.4 ng/ml to 268.9 ng/ml. After administration of the Feug Ya Dzal mix, the CEA value decreased to 144 ng/ml. There was a 53% noticeable decrease in the value obtained within a month. We report the ATM management of tumors using safe doses’, noninvasive, non-hormonal indigenous science based interventions alone or combined with conventional therapies.

Keywords: African medicine, fibroid, uterine fibroid, myoma, fibromyoma, tumor plant treatment, colon cancer, tumor

BACKGROUND

In Africa, morbidity and mortality are rising due to non-infectious diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and while the burden of communicable diseases is falling [1]. Cancer is now the fifth leading cause of death in Africa [1], which warrants further investigation about new cancer fighting agents. In Africa, there was an estimated 1.1 million new cancer cases and 711,429 deaths occurred due to neoplasms in 2020 [2]. In Cameroun, around 20,745 new cancer cases were recorded with an estimated 13,199 deaths recorded the same year. Egypt was the leading country with 134,632 new cases and 89,042 deaths; Nigeria was ranked second, followed by South Africa, with an estimated incidence of 124,815 and 108,168, respectively. Egypt (89,042 deaths), Nigeria (78,899 deaths), and South Africa (56,802 deaths] were the top three ranked countries in terms of cancer deaths. The burden of all neoplasms combined is forecasted to increase to 2.1 million new cases and 1.4 million deaths in Africa [2].

Benign tumors and malignant neoplasms may share etiologic factors and clinical manifestations that affect quality of life or life expectancy [3]. Some are known cancer precursors, including for example colorectal adenoma [4]and thyroid nodules [5]. Others are benign and noncancerous, yet significantly impact women’s health and quality of life, such as uterine fibroids (UFs) [6] Uterine fibroids also known as uterine leiomyoma, fibromyoma or myoma, are the most common solid benign tumors affecting millions of women of reproductive age of all races. They are the most common benign pelvic tumors in women, and may affect up to 70% of all women by menopause [7-9]. UFs have been classified according to their general uterine position: submucous, intramural, and subserosal. Intramural fibroids are located within the wall of the uterus and are the most common type. Though the exact cause of intramural fibroids is unknown, it is believed that fibroids develop from an abnormal muscle cell in the middle layer of the uterine wall. The cell rapidly multiplies and forms a tumor influenced by estrogen [10]. Fibroid risk factors include race, age, family history, time since last birth, premenopausal state, hypertension, and diet [11]. Based on ultrasonography, the estimated cumulative incidence of fibroids in women ≤50 years is significantly higher for black (>80%) versus white women (∼70%) [12] in the United States. The highest burden of this condition affects black women, occurring at rates 3–4 times greater in them as compared to their counterparts of other races. It is estimated that 70–80% of black women will harbor fibroids over their lifetime [13-14]. It is also estimated that approximately 25% to 50% of women with fibroids are symptomatic, experiencing heavy menses, reproductive issues, pain, increased urinary frequency, and anemia [15-16]. Low back pain; fullness in the lower abdomen, infertility, multiple miscarriages, or early onset of labor during pregnancy are also reported. There is a general lack of awareness of fibroids among women and their potential health impact [17]. Uterine fibroid symptoms negatively impact women's activities, quality of life [18], and work productivity [19-20]. Black women experience fibroids at an earlier age, have more severe symptoms [21], and increased disease burden [22]. The overall economic burden of symptomatic fibroids is estimated at $5.9–34.4 billion USD annually in the USA in both direct costs (e.g., medications, inpatient/outpatient visits, and surgery) and indirect costs (e.g., lost work time and preterm delivery) [23-24]. There is very scarce information as to the economic impact on Sub-Saharan Africa. Due to insufficient knowledge and access to care and late presentation, many women in Africa suffer greater morbidity and oftentimes-higher rates of mortality from fibroid disease.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, most treatments for symptomatic uterine fibroids involve myomectomy, a procedure that can result in post-operative complications including hemorrhage, shock, fever, wound infection, and subsequent dehiscence, culminating in extended hospitalizations [25]. Other consequences include destruction of endometrium during fibroid enucleation especially when fibroids are multiple in number and bulky - causing amenorrhea and iatrogenic infertility in reproductive-aged women. For these reasons and more, African women prefer other less invasive options rather than surgery [7]. Medications are being investigated as potential oral alternatives to surgery in the management of fibroids such as selective progesterone receptor modulators and oral nonpeptide gonadotrophin releasing hormone antagonists [26-27]. Most of these interventions are currently too expensive for women residing in resource-limited settings like those of Sub-Saharan Africa. Besides, patient follow-up and rigid compliance regimens that these interventions may require make them less than optimal options [7]. In the management of African women with fibroids, cost containment is of pivotal importance. Therefore, considerable thought must be given to the development of low-cost interventions that could achieve a higher rate of compliance. For that purpose, the importance of safe plant remedies is valuable. Moreover, research outcome on polyherbal African antitumor medicine is very rarely documented, unlike that of Chinese [28], Korean [29] or Ayurvedic [30] traditional medicines. We failed to record any in the literature despite various numerous articles on African antitumor plants. Hence the need to evaluate African polyherbal formulas used for uterine fibroid and other tumors’ management, and trigger more documentation such as the present report cases

1. FIBROID CASE STUDY

A 33-year-old female patient, reported to the outpatient department of SOS AMY clinics on the first of October 2019 with complaints of pain and uncomfortable mass in the pelvic area that she could feel when lying down on her back. She complained of lower abdominal aches but normal menstrual bleeding. She had a very active lifestyle. She was previously diagnosed with Fibroids from the prior reports and was advised to have them surgically removed (laparotomy, myomectomy). She was born in a family of 5 girls with ages ranging from 24 to 42 years old. All 4 of her female siblings developed fibroids. No other systemic complaints related to this condition were significant.

CLINICAL FINDINGS GENERAL EXAMINATION

All vitals were stable on examination. The abdominal examination revealed a soft, non-tender abdomen and no organomegaly was detected.

INVESTIGATION

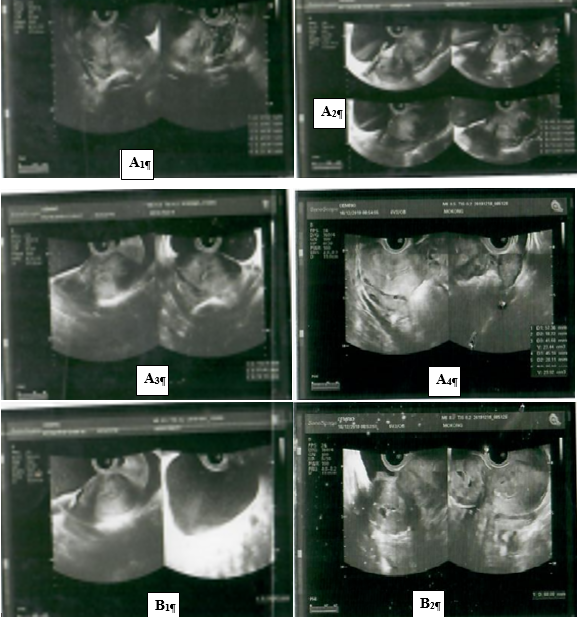

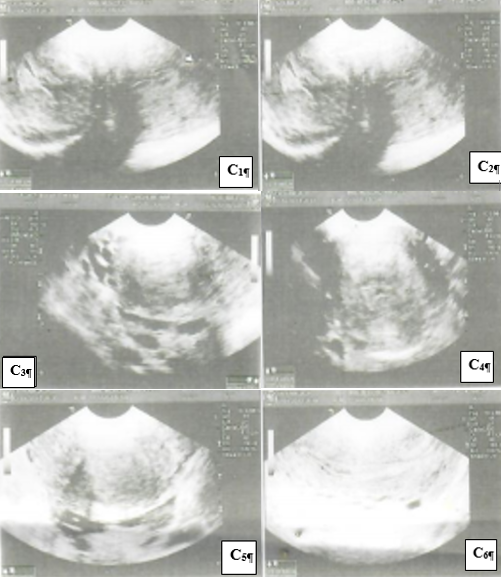

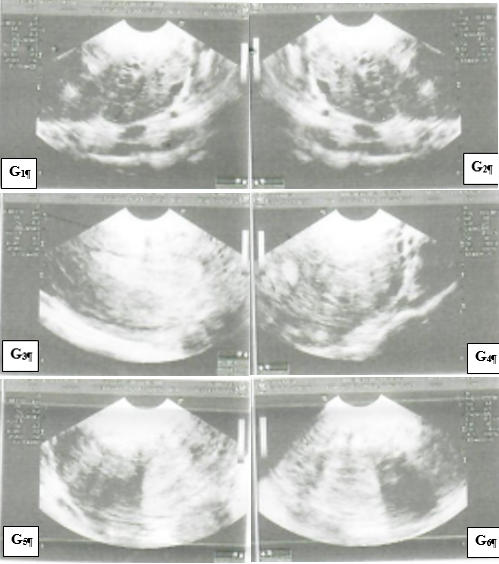

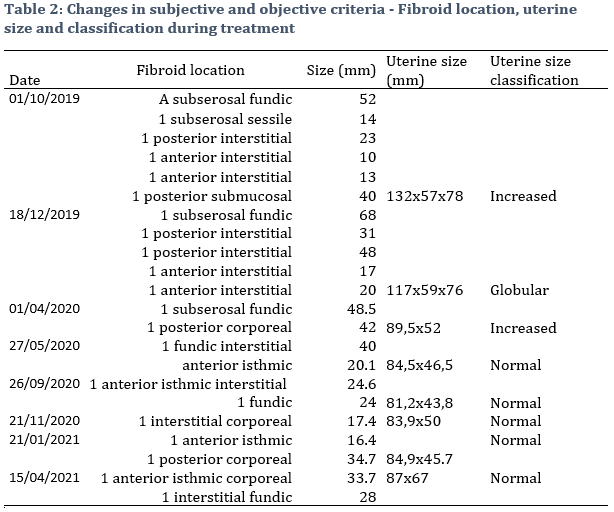

The ultrasound scan of her Abdomen & Pelvis on October 1st, 2019 revealed a non-gravid uterus of increased size measuring 132 x 57 x 78 mm, with regular contours and heterogeneous myometrium. We noted the presence of 06 polymyomatous nuclei including 01 fundic subserous in necrobiosis of 52 mm, 01 anterior sessile subserous of 14 mm, 01 posterior interstitial of 23 mm, 01 posterior submucous of 40 mm, 02 anterior interstitials of 10 and 13 mm. The endometrium was heterogeneous and thickened to 19 mm. The right and left ovaries were of normal size and measured 37 x 20 x 28 mm and 41 x 24 x 31 mm, respectively. The annexes were free. There was an absence of fluid effusion in the pouch of Douglas. The bladder was of normal size, thin-walled, with transonic content.

DIAGNOSIS

On October 1st 2019, the clinical features along with the ultrasound scan report suggested an enlarged uterus with 6 polymyomatous nuclei. There was heterogeneous thickening of the endometrium which could require hysterosonography. The ultrasound device used was the LOGIC E of the General Electric brand with endocavitary probe frequency E8C 6.5 to 7.5 Hz and a SONY brand printer.

On April 1st, 2020, hysterosalpingography revealed a normal-sized uterine cavity with regular and retroverted contours, as well as left distal tubal obstruction with hydrosalpinx sequelae of left chronic salpingitis and unsatisfactory pelvic passages.

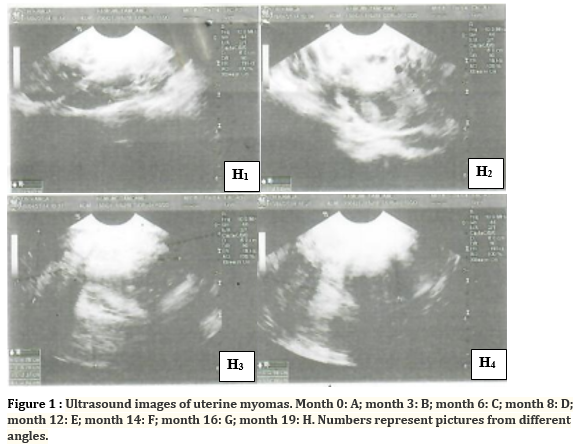

THERAPEUTIC INTERVENTIONS FOR FIBROID TREATMENT AND OUTCOME

The patient was recommended to pursue a surgical removal of fibroids (laparotomy and myomectomy) however, she was not willing to undergo surgery and was in quest of nonhormonal treatment. Based on African Traditional management of fibroids, we formulated a regimen from medicines available at the SOS AMY Clinic for her to complete. She was advised to take the following medicines for a period of 6 months to observe changes (Table 1). She was also advised to decrease sugar intake. The fibroid treatment was scheduled initially for 6 months with a follow up once a month and ultrasound exams every 2 to 4 months. The following conventional medicines were prescribed to treat salpingitis: Orilox (Cefpodoxime 500, 1 tablet twice a day) and Dicloberl (100 MG, 1 suppository twice a day) for 10 days.

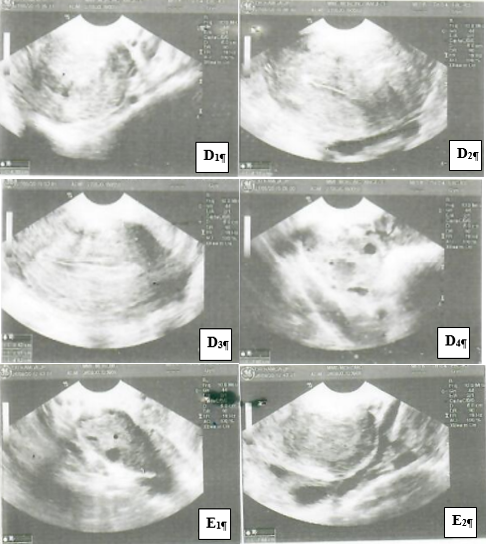

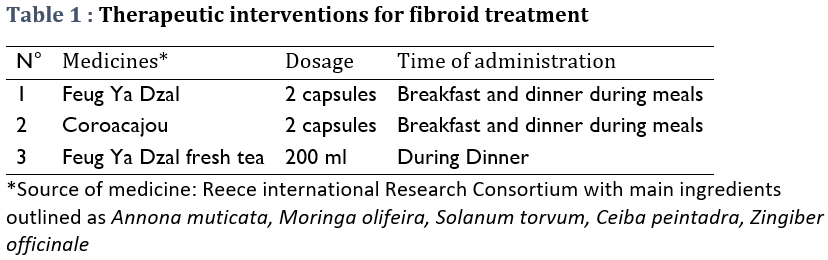

During the month of November 2020, there was a shortage of capsules due to COVID19 related import restrictions (Cameroon does not manufacture empty capsules and users have to import them from abroad). The treatment was modified. The patient had to take 1 teaspoon of the products’ powders in replacement of capsules. The patient also experienced difficulties adapting to the product’s taste, and difficulties adhering to the treatment doses and frequency. She stopped the treatment when the ultrasound exam interpretation revealed the remaining myomas could not interfere with an eventual pregnancy. The patient also reported that the discomfort and pain had also waned. Indeed, during treatment the fibroid number was reduced from 6 to 2 within 6 months (Figure 2).

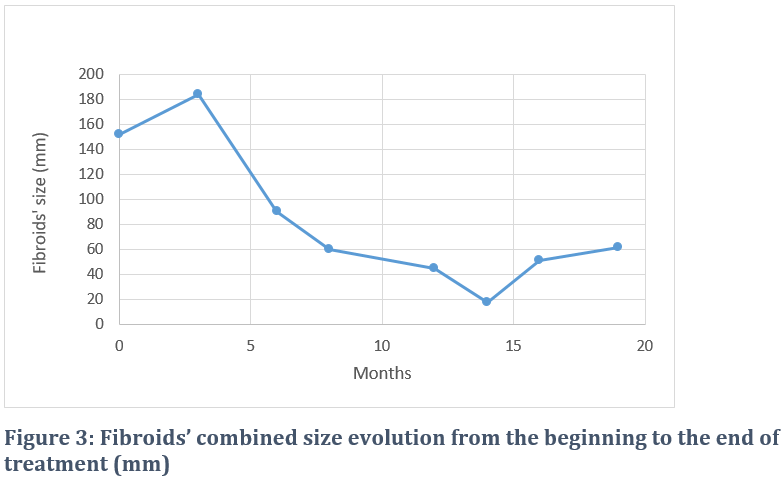

During care, besides monitoring fibroids’ numbers by both pelvis and endovaginal ultrasound, their combined size was also monitored and was found to be decreasing over time from 152 mm to 60.1 mm within 8 months (Figure 3), and to 17.4 mm within 14 months. However, there was an increase in size following capsule shortage. The fibroids combined size decreased by a factor of 2.5.

Changes in fibroids’ number and size was accompanied by the reduction of the uterine dimensions, from increased and globular to normal size (Table 2). There was a remarkable involution during treatment. Indeed, there was a 34.1% decrease in the uterus length at the end of the treatment period. Ultrasound also revealed the disappearance of the submucosal myoma during the same period.

2. COLORECTAL CANCER CASE STUDY

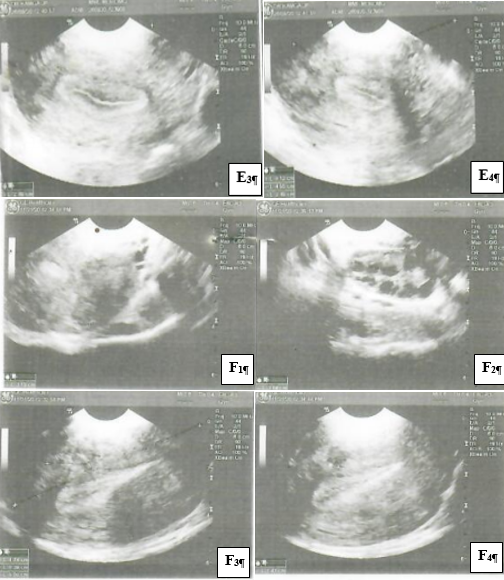

A 58-year-old male patient under chemotherapy requested complementary medicine for his treatment. He was diagnosed as suffering from a stage IV colon cancer. He experienced abdominal pain, weight loss and fatigue. Chemotherapy drugs were used to shrink tumors and ease colon cancer. However, there was no apparent improvement observed for the patient. On August 13, 2020, the patient demanded herbal complementary medicine.

CLINICAL FINDINGS EXAMINATIONS

Clinical examinations revealed the patient had a hemoglobin level of 10.4 g/dl, which was severely low (normal 14-17.5 g/dl in males).In humans, anemia is defined by one of the following: Hemoglobin < 14 g/dL (140 g/L), Hematocrit < 42% or RBC < 4.5 1012/L. Chemotherapy may affect bone marrow cells, reducing their production of red blood cells. The patient’s red blood cell count was 3.65 x 1012/L, interpreted as being low. The normal red blood cell count in adult males ranges between 4.0 and 5.9 x 1012/L. His fasting blood glucose level was 1.16 g/l. A fasting blood glucose from 1 to 1.25 g/L (5.6 to 6.9 mmol/L is usually classified as prediabetes). Markers used to monitor his chemotherapy treatment outcome included CEA and CA19-9. Levels of the two markers were 268.9 ng/ml (Normal : < 5 ng/ml) and 4.79 U/ml (Normal: < 39 U/ml) respectively. The carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) test measuring CEA, a specific blood protein, revealed a highly elevated value. Usually, people are born with high CEA levels that decrease as they get older. But some types of cancers can increase the levels of this protein. Healthcare providers used the CEA test to guide his cancer treatment and to see if treatment was working. The normal range of CA 19-9 is usually between 0 and 37 U/mL (units/milliliter).

INVESTIGATION

The available patient file was analyzed as from the second of July 2020. In addition to generic follow up, six markers were used in order to monitor both chemotherapy and complementary treatments sought by the patient. These markers were the Hemoglobin level (HGB), red blood cell count, fasting blood glucose, CEA and CA 19-9. Tests were performed at the Pasteur Institute. The serological Enhanced “Chemiluminiscence” Immunoassay (ECLIA) method was used to assess markers’ levels.

COMPLEMENTARY TREATMENT OF COLON CANCER AND OUTCOME

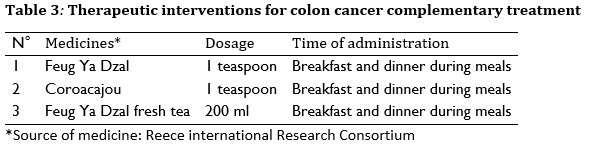

The patient was given the Feug Ya Dzal polyherbal mix as outlined in table 3.

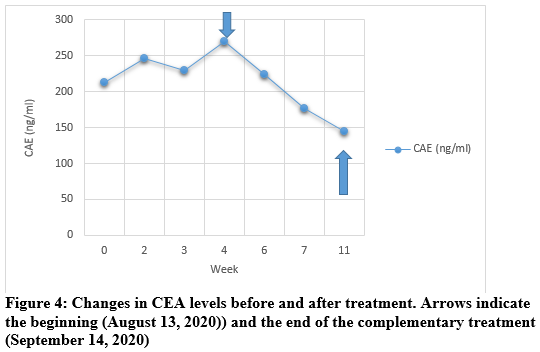

The patient monitoring was performed without any change even though complementary medicine was added. The same markers were tested (Figure 4 and Table 4). While the patient was going through chemotherapy alone, the CEA value monitored from July second 2020 to the 31st of July 2020, increased from 212.4 ng/ml to 268.9 ng/ml. After requesting the addition of the Feug Ya Dzal mix on August 13, 2020, the CEA value decreased to 144 ng/ml (value measured the September 9, 2020). There was a 53% decrease in the value obtained before treatment (Figure 4).

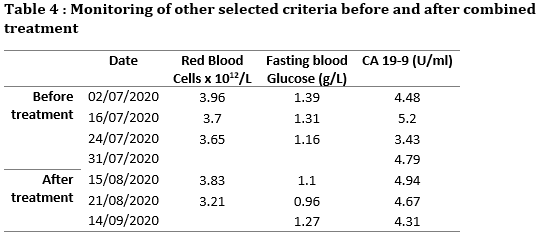

Other vital markers were also monitored. There was no observed change or improvement in red blood cell count, fasting blood glucose and CA 19-9 (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

Uterine fibroids also known as uterine leiomyomas or myomas are non-cancerous growths in the uterus. Although many women with fibroids are not aware of them, they may cause symptoms or problems due to their size, number, or location. Common symptoms can include longer or more frequent menstrual periods, heavy bleeding, menstrual pain, pressure in the lower abdomen, infertility, or miscarriages. Fibroids can be treated with surgery, such as myomectomy or hysterectomy which is the removal of the uterus. They can also be treated by artery embolization, where blood vessels to the uterus are blocked. Drugs such as gonadotropin‐releasing hormone agonists may be also be used to shrink fibroids and to control bleeding.

Several pharmacological agents are available to reduce the size of fibroids and ameliorate the symptoms. However, these drugs are expensive and are usually associated with profound side effects. Thus, botanical drugs are gaining attention in this era due to their cost effectiveness with a comparable and more potent therapeutic efficacy while demonstrating lesser adverse effects [31]. Surgical techniques and aggressive treatments are reserved for only those cases with heavy symptomatology, while Herbal preparations are commonly used alternatives to drug treatment or surgery.

In this case study, traditional African medicine was found to be effective by reducing myoma numbers by 67%. The overall size of uterine myomas reduced by about 59% corresponding to a 9 cm decrease. There was also a remarkable involution during treatment. Uterus changed from increased, globular to normal size. In general, uterine involution is a significant change that allows women to regain some comfort because their increased size uterus shrinks during involution.

In the 58-year-old male colon cancer case, the same cytotoxic medicine was able to reduce the CEA marker by 53% in one month, which, chemotherapy failed to attain alone. This strengthens the observation in other studies that complementary medicine associated with modern medicines leads to improved fibroid or cancer respective treatment results or health outcome [32-33]. Many of the anticancer agents that are currently in use demonstrate severe side effects and encounter increasing resistance from the target cancer cells. There is therefore still a need to develop new, alternative anticancer agents. The plant kingdom contains a wide range of phytochemicals that play important roles in the prevention and treatment of many diseases. Literature highlights the antitumor activity of plant extracts and their synergistic effect with chemotherapeutic agents in various in vitro and in vivo cancer models [34]. They could be proposed as alternative and complementary treatments instead of invasive surgery. For that purpose, information on the advantages and disadvantages of various treatments should be provided. In traditional African medicine, herbal solutions such as Feug Ya Dzal are chosen as a standard traditional practice in treating uterine myoma or other tumors. However, research outcome on polyherbal African antitumor medicine is very rarely documented, unlike that of Chinese [28], Korean [29] or Ayurvedic [30] traditional medicines. We failed to record any in the literature despite various numerous articles on African antitumor plants. Hence the need to report the present cases. The main constitutive herbs of Feug Ya Dzal are : 1) Ceiba pentandra that has been shown to display significant antitumor activity in both in vitro and in vivo system. Its cytotoxic effect on EAC cells and long term cytotoxic effect on human breast cancer cell line (MCF-7) and melanoma cell line (B16F10), supported by protection to the hemopoietic system along with elevation of the endogenous antioxidant defense system, might play an important role in the antitumor activity [35]; 2) Annona muricata whose compounds (Phenolics, Alkaloids, Cyclopeptides, Megastigmanes, Flavonol triglycosides, Minerals, Annonaceous acetogenins and Essential oils) have proven to be cancer-fighting agents. Bioactive metabolites present in A. muricata, their role in affecting the growth and death of different cancer cell types, the molecular mechanism of how it works to downregulate anti-apoptotic genes and the genes involved in pro-cancer metabolic pathways have been described. A. muricata’s phytochemicals simultaneously increase the expression of genes promoting apoptosis and cause cancer cells to die [36]; 3) Moringa olifeira whose alkaloid extracts have been shown to exert antitumor activity in Human Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer via modulation of the JAK2/STAT3 Signaling Pathway [37]. It has also been demonstrated that cell death percentage of mononuclear leukemic and HepG2 cells treated with the Moringa extract is approximately 75% compared to the control [38]; 4) Solanum torvum that contains many phenolic compounds such as Solasodine that bind to the BCL2 protein receptor and cause apoptosis thereby successfully killing Ehrlich’s Ascites Carcinoma cell Lines [39]; 4) Zingiber officinale whose studies on antitumor effect suggest that the reduction of cell viability and apoptosis by its leaf may be a result of ATF3 promoter activation and subsequent increase of ATF3 expression through ERK1/2 activation in human colorectal cancer cells [40]. The limited success of clinical therapies, and the immense side effects of synthetic anticancer drugs, took into drug discovery from medicinal plants which have played an important role in the treatment of cancer. In fact, in the area of cancer, over the time frame from around the 1940s to date, of the 175 small molecules, 131, or 74.8%, are other than synthetic, with 85, or 48.6%, actually being either natural products or directly derived therefrom [41]. The present study meets the growing need for alternate approach of either combining several drugs or designing additional natural drugs that may simultaneously influence multiple targets to trigger a cascade of protective events complementing one another.

In conclusion, the findings of this study demonstrated the success case of African polyherbal medicines in fibroid shrinking, in tumor marker reduction and relief of fibroid-related symptoms. The female patient reported significant decrease in discomfort and improved quality of life. It was confirmed that the traditional drug regimen seems safe under regimen doses (toxicity data in press) for use in uterine fibroid treatment and to strengthen chemotherapy interventions. Despite the fact that the patient did not fully adhere to the treatment, there was still a significant decrease in fibroid size. These results suggest that more studies with patients undergoing stricter regimens may yield even stronger results. Furthermore, we suggest that randomized controlled trials are needed to confirm our findings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors are grateful to Dr Jean Pierre Kamga, Physician Radiologist, for performing routine ultrasonography. Dr Kamga is Specialist in radiodiagnosis and medical imaging (Ultrasonography, Scanner, MRI), AFS of radiology of the Faculty of medicine of Brest (France), Former Attaché of Radiology at the University Hospital of Brest and at the Pitié Salpetrière in Paris (France).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Authors declare no conflict of interest. SOS AMY Clinics’ researchers may provide assistance in both the development of improved traditional medicines and related research.

REFERENCES

1. Roth, G.A., Abate, D., Abate, K.H. (2018). ‘Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017’. Lancet 392:1736–88. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32203-7.

2. Sharma, R., Aashima, Nanda, M., Fronterre, C., Sewagudde, P., Ssentongo, A.E., et al. (2022). ‘Mapping Cancer in Africa: A Comprehensive and Comparable Characterization of 34 Cancer Types Using Estimates From GLOBOCAN 2020’. Front Public Health. Apr 25;10:839835. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.839835. PMID: 35548083.

3. Bowers, D.C., Moskowitz, C.S., Chou, J.F., et al. (2017). ‘Morbidity and mortality associated with meningioma after cranial radiotherapy: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study’. J Clin Oncol.;35(14):1570-1576. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.1896.

4. Leslie, A., Carey, F.A., Pratt, N.R. and Steele, R.J. (2002). ‘The colorectal adenoma-carcinoma sequence’. Br J Surg.;89(7):845-860. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02120.x.

5. Arora, N., Scognamiglio, T., Zhu, B. and Fahey, T.J. III (2008). ‘Do benign thyroid nodules have malignant potential? an evidence-based review’. World J Surg.;32(7):1237-1246. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9484-1.

6. Hervé, F., Katty, A., Isabelle, Q. and Céline, S. (2018). ‘Impact of uterine fibroids on quality of life: a national cross-sectional survey’. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. Oct;229:32-37. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.07.032.

7. Igboeli, P., Walker, W., McHugh, A., Sultan, A. and Al-Hendy (2019). ‘A. Burden of Uterine Fibroids: An African Perspective, A Call for Action and Opportunity for Intervention’. Curr Opin Gynecol Obstet.;2(1):287-294. doi: 10.18314/cogo.v2i1.1701.

8. Drayer, S.M., Catherino, W.H. (2015). ‘Prevalence, morbidity, and current medical management of uterine leiomyomas’. Int J Gynaecol Obstet;131:117–122.

9. Stewart, E.A., Cookson, C., Gandolfo, R.A. and Schulze-Rath, R. (2017). ‘Epidemiology of uterine fibroids: A systematic review’. BJOG 124:1501–1512.

10. Moravek, M.B. and Bulun, S.E. (2015). ‘Endocrinology of Uterine Fibroids: Steroid Hormones, Stem Cells, and Genetic Contribution’. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 27(4):276–283.

11. Stewart, E.A., Laughlin-Tommaso, S.K., Catherino, W.H., Lalitkumar, S., Gupta, D. et al. (2016). ‘Uterine fibroids’. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2:16043.

12. Baird, D.D., Dunson, D.B., Hill, M.C., Cousins, D. and Schectman, J.M. (2003). ‘High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: Ultrasound evidence’. Am J Obstet Gyneco l;188:100–107.

13. Al-Hendy, A. and Salama, S.A. (2006). ‘Ethnic distribution of estrogen receptor-α polymorphism is associated with a higher prevalence of uterine leiomyomas in black Americans’. Fertil Steril.;86(3):686–693. Doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.01.052.

14. Vercellini, P. and Frattaruolo, M. (2017). ‘Uterine fibroids: From observational epidemiology to clinical management’. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gy.;124(10):1513–1513. Doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14730.

15. Bartels, C.B., Cayton, K.C., Chuong, F.S., et al. (2016). ‘An evidence-based approach to the medical management of fibroids: A systematic review’. Clin Obstet Gynecol;59:30–52.

16. Khan, A.T., Shehmar, M. and Gupta, J.K. (2014). ‘Uterine fibroids: Current perspectives’. Int J Womens Health;6:95–114.

17. Ghant, M.S., Sengoba, K.S., Vogelzang, R., Lawson, A.K. and Marsh, E.E. (2016). ‘An altered perception of normal: Understanding causes for treatment delay in women with symptomatic uterine fibroids’. J Womens Health (Larchmt);25:846–852.

18. Fortin C., Flyckt R. and Falcone, T. (2017). ‘Alternatives to hysterectomy: The burden of fibroids and the quality of life’. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol.;46:31–42. Doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2017.10.001.

19. Ghant, M.S., Sengoba, K.S., Recht, H., Cameron, K.A., Lawson A.K. and Marsh, E.E. (2015). ‘Beyond the physical: A qualitative assessment of the burden of symptomatic uterine fibroids on women's emotional and psychosocial health’. J Psychosom Res;78:499–503.

20. Zimmermann, A., Bernuit, D., Gerlinger, C., Schaefers, M. and Geppert, K. (2012). ‘Prevalence, symptoms and management of uterine fibroids: An international internet-based survey of 21,746 women’. BMC Womens Health; Mar 26;12:6. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-12-6.

21. Stewart, E.A., Nicholson, W.K., Bradley, L. and Borh, B.J. (2013). ‘The burden of uterine fibroids for African-American women: Results of a national survey’. J Womens Health (Larchmt);22:807–816.

22. Sengoba, K.S., Ghant, M.S., Okeigwe, I., Mendoza, G., Marsh, E.E. (2017). ‘Racial/Ethnic Differences in Women's Experiences with Symptomatic Uterine Fibroids: A Qualitative Assessment’. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities; 4:178–183.

23. Cardozo, E.R., Clark, A.D., Banks, N.K., Henne, M.B., Stegmann, B.J. and Segars, J.H. (2012). ‘The estimated annual cost of uterine leiomyomata in the United States’. Am J Obstet Gynecol;206:211.e211–e219.

24. Marsh, E.E., Al-Hendy, A., Kappus, D., Galitsky, A., Stewart, E.A. and Kerolous, M. (2018). ‘Burden, Prevalence and Treatment of Uterine Fibroids: A Survey of U.S. Women’. J Womens Health (Larchmt). Nov;27(11):1359-1367. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2018.7076.

25. Adesina, K.T., Owolabi, B.O., Raji, H.O., et al. (2017). ‘Abdominal myomectomy: A retrospective review of determinants and outcomes of complications at the university of ilorin teaching hospital, Ilorin, Nigeria’. Malawi Med J.;29(1):37–42.

26. Archer, D.F., Stewart.A., Jain, R.I., et al. (2017). ‘Elagolix for the management of heavy menstrual bleeding associated with uterine fibroids: Results from a phase 2a proof-of-concept study’. Fertil Steril.;108(1):152–160.e4. Doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.05.006.

27. Puchar, A., Luton and D., Koskas, M. (2015). ‘Ulipristal acetate for uterine fibroid-related symptoms’. Drugs Today (Barc). Nov;51(11):661-7. doi: 10.1358/dot.2015.51.11.2413469.

28. Luo, L. and Zhu, Y.P. (2003). ‘Effect of treating 110 cases of uterine fibroids with the use of Qing Gong Liu capsules’. Chinese Journal of Traditional Medical Science and Technology;10(6):382–383.

29. Lim, C.H. and Yoo, J.E. (2018). ‘A case report of traditional Korean medicine treatments on uterine myoma with thyroid cancer’. Integr Med Res. Dec;7(4):303-306. doi: 10.1016/j.imr.2018.10.003.

30. Shubhashree, M.N., Doddamani, S.H., Bhavya, B.M., et al. (2019). ‘Successful management of uterine fibroids by Ayurvedic treatment’. Int J Complement Alt Med.;12(6):257-260 DOI: 10.15406/ijcam.2019.12.00483.

31. Arip, M., Yap, V.L., Rajagopal, M., Selvaraja, M., Dharmendra, K. and Chinnapan, S. (2022). ‘Evidence-Based Management of Uterine Fibroids with Botanical Drugs-A Review’. Front Pharmacol.; Jun 22;13:878407. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.878407.

32. Dalton-Brewer, N. (2016). ‘The Role of Complementary and Alternative Medicine for the Management of Fibroids and Associated Symptomatology’. Curr Obstet Gynecol Rep.; 5:110-118. doi: 10.1007/s13669-016-0156-0.

33. Wang, Z., Qi, F., Cui, Y., Zhao, L., Sun, X., Tang, W. and Cai, P. (2018). ‘An update on Chinese herbal medicines as adjuvant treatment of anticancer therapeutics’. Biosci Trends;12(3):220-239. doi: 10.5582/bst.2018.01144.

34. Kowalczyk, T., Merecz-Sadowska, A., Rijo., Mori, M., Hatziantoniou, S., Górski, K. et al. (2022). ‘Hidden in Plants-A Review of the Anticancer Potential of the Solanaceae Family in In Vitro and In Vivo Studies’. Cancers (Basel). Mar 11;14(6):1455. doi: 10.3390/cancers14061455.

35. Kumar, R., Kumar, N., Ramalingayya, G.V., Setty, M.M. and Pai, K.S. (2016). ‘Evaluation of Ceiba pentandra (L.) Gaertner bark extracts for in vitro cytotoxicity on cancer cells and in vivo antitumor activity in solid and liquid tumor models’. Cytotechnology. Oct;68(5):1909-23. doi: 10.1007/s10616-016-0002-2.

36. Ilango S, Sahoo DK, Paital B, Kathirvel K, Gabriel JI, Subramaniam K, Jayachandran P, Dash RK, Hati AK, Behera TR, Mishra P, Nirmaladevi R. A Review on Annona muricata and Its Anticancer Activity. Cancers (Basel). 2022 Sep 19;14(18):4539. doi: 10.3390/cancers14184539.

37. Xie, J., Peng L.-J., Yang M-R., Jiang, W.W., Mao,J.Y., Shi, C.Y., Tian, Y. and Sheng, J. (2021). ‘Alkaloid Extract of Moringa oleifera Lam. Exerts Antitumor Activity in Human Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer via Modulation of the JAK2/STAT3 Signaling Pathway’. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, vol. 2021, Article ID 5591687, 12 pages. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5591687.

38. Abd-Rabou, A.A., Abdalla, A.M., Ali, N.A., Zoheir, K.M. (2017). ‘Moringa oleifera Root Induces Cancer Apoptosis more Effectively than Leave Nanocomposites and Its Free Counterpart’. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. Aug 27;18(8):2141-2149. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.18.8.2141.

39. Panigrahi, S., Muthuraman, M.S., Natesan, R., & Pemiah, B. (2014). ‘Anticancer activity of ethanolic extract of Solanum torvum sw’. International Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences. ISSN- 0975-1491 Vol 6, Suppl 1.

40. Park, G.H., Park, J.H., Song, H.M., Eo, H.J., Kim, M.K., Lee, J.W., et al. (2014). ‘Anti-cancer activity of Ginger (Zingiber officinale) leaf through the expression of activating transcription factor 3 in human colorectal cancer cells’. BMC Complement Altern Med. Oct 23;14:408. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-408.

41. Newman, D.J. and Cragg, G.M. (2012). ‘Natural products as sources of new drugs over the 30 years from 1981 to 2010’. J Nat Prod. Mar 23;75(3):311-35. doi: 10.1021/np200906s.

AUTHORS' AFFILIATION

1Department of pharmacy, University of Liège, Belgium

2 Child Health Associate PA Program, University of Colorado, Aurora Colorado, USA

3SOS AMY Clinics, Yaoundé, Cameroon

4Department of Biochemistry, University of Yaounde I, Cameroon